Page 1 of 2

Chapters 4-6: Up From Slavery

Posted: Tue Apr 05, 2016 9:26 am

by Chris OConnor

Chapters 4-6: Up From Slavery

Please use this thread for discussing Chapters 4-6: Up From Slavery.

Re: Chapters 4-6: Up From Slavery

Posted: Sat Apr 23, 2016 9:38 pm

by LanDroid

The "Ku Klux" period was, I think, the darkest part of the Reconstruction days. I have referred to this unpleasant part of the history of the South simply for the purpose of calling attention to the great change that has taken place since the days of the "Ku Klux." To-day there are no such organizations in the South, and the fact that such ever existed is almost forgotten by both races. There are few places in the South now where public sentiment would permit such organizations to exist. (p. 30 end chapter 4)

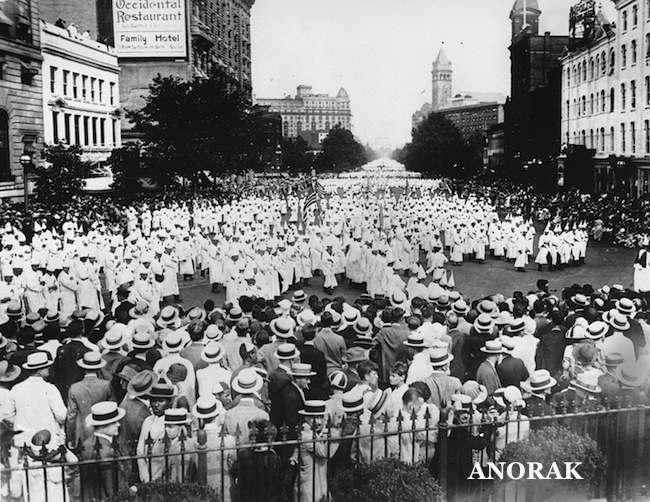

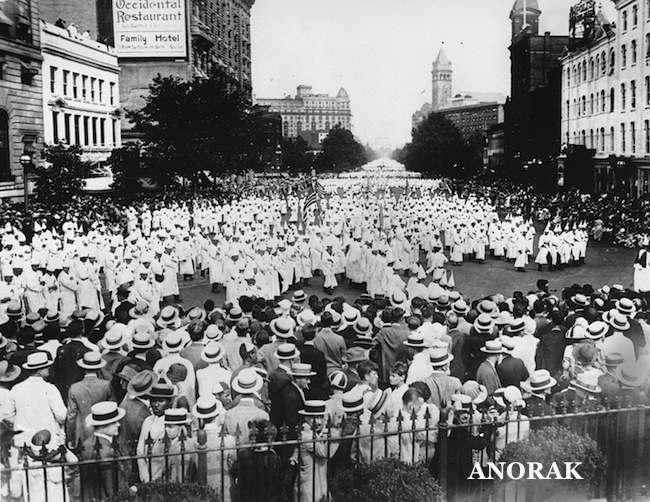

This seems outrageous, but might be kinda-sorta of true. Founded in 1865, the KKK influence had reduced significantly by 1901. However there was a major revival in 1915 (after D.W. Griffith's movie "Birth of a Nation") and by the mid-1920's there were 4 million members. In 1925 50000 to 60000 members marched in Washington DC as a show of power. It didn't take much for the KKK to come roaring back, so I think Washington grossly over-stated the situation above.

See below, it doesn't appear the huge audience was there to shout them down...

Re: Chapters 4-6: Up From Slavery

Posted: Sat Apr 23, 2016 9:53 pm

by Taylor

LanDroid wrote:To-day there are no such organizations in the South, and the fact that such ever existed is almost forgotten by both races.

I'm just considering this small portion of the Booker T quote, There is an odd sort of outrageousness, Its like a denial of rural south realities(after thought: Not just the south). Its seems a given that remnants of the KKK have been and will be always around, Its almost naïve to document otherwise.

Re: Chapters 4-6: Up From Slavery

Posted: Wed Apr 27, 2016 6:48 am

by LevV

Booker T Washington begins chapter five on what he sees as the shortcomings of the Reconstruction period. He describes how Blacks used education as an avenue to escape a life of manual labor resulting in many entering the fields of the ministry, education and politics ill prepared for the jobs with a bare minimum of education. As such, he continues to drive home his main message that the more practical road to success for his race must be through industrial training.

I've been looking to other sources to try to get a more complete picture of Booker T during this period of his life. "From Plantation to Ghetto" by August Meier and Elliott Rudwick has been very enlightening, especially chapter V with the title "Up from Slavery: The Age of Accommodation". The authors point out the irony in Washington's emphasizing his choice not to enter politics while he was to eventually wield more political power than any Black American of his time! He even had a very close relationship with Theodore Rosevelt who apparently consulted Washington regularly on race matters in the South. It seems he also exerted considerable influence through his connections with a number of Black newspapers.

It should be noted that his non-confrontational approach was beginning to test the patience of other Black leaders in the African American community who thought that more action should be taken to advocate for civil rights.

Re: Chapters 4-6: Up From Slavery

Posted: Mon May 02, 2016 3:29 pm

by LevV

In chapter six we see Washington broadening his teaching experiences further. At the request of general Armstrong he agrees to teach a group of American Indians and to live with them as a "house father".

His description of the Indians he is working with is interesting. He describes them as, "wild and for the most part ignorant" showing that he is also capable of holding stereotypes of other peoples. And he goes on to state that he "knows that the average Indian felt himself above the white man, and, of course, he felt himself far above the Negro, largely on account of the Negro having submitted to slavery - a thing which the Indian would never do".

It is also interesting how he chose to write about theincident where he is the victim of racism when the Indian boy he was with on the steamboat could be served dinner but he couldn't be served. He describes the incident without any anger in his tone, but we are, at the same time, left with an appreciation of the huge racial challenges he faced.

Re: Chapters 4-6: Up From Slavery

Posted: Thu May 05, 2016 3:16 pm

by DWill

Washington strikes me as an extremely disciplined man, both in the way in which he applied himself to his goals and the way that he sticks to his message, refusing to be led into controversies. It surprises me that only once in the book that I can recall does he refer to the major differences between him and someone like Dubois. Even then, the reference is oblique. He thought that the whites' desire to remain separate socially from the Negro was acceptable, or at least that it would be counter-productive to demand this type of equality up front. He had this serene faith that if the Negro race would patiently apply itself to all the useful arts, that ability would have to be recognized and accorded great respect by the white race, which then might forge social equality. He was certainly an optimist, which probably enabled him to avoid becoming discouraged in the face of obstacles that he couldn't help but recognize.

Re: Chapters 4-6: Up From Slavery

Posted: Sat May 07, 2016 9:02 am

by LevV

DWill wrote:It surprises me that only once in the book that I can recall does he refer to the major differences between him and someone like Dubois. Even then, the reference is oblique. He thought that the whites' desire to remain separate socially from the Negro was acceptable, or at least that it would be counter-productive to demand this type of equality up front. He had this serene faith that if the Negro race would patiently apply itself to all the useful arts, that ability would have to be recognized and accorded great respect by the white race, which then might forge social equality.

Washington had an agenda, to build Tuskagee into the successful institution for Black vocational training that it became. He knew that in order to overcome the incredible obstacles that lay ahead, he would require the support and resources of rich white people and that meant telling them what they wanted to hear. This included his agreeing to segregation, not insisting upon the vote, not opposing property requirements or literacy tests etc. In fact, many people feel that his support for segregation in the Atlanta Compromise address may have contributed to the 1896 Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v Ferguson, in favor of the legality of separate but equal public facilities for Blacks and whites.

Du Bois, on the other hand, spent a lifetime fighting for full citizenship for Blacks. Here was an African American with a superior intellect and educated at Fisk, Harvard and Heidelberg. His understanding and analysis went beyond the economic, social and political. He understood and was clearly deeply troubled by the psychological damage to Blacks with segregation. From "The Souls of Black Folk":

"It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One even feels his two-ness, - an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unrecognized strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder".

What was critical for Du Bois was that Blacks, while seeking admission to white society, not sacrifice their racial heritage and individuality:

"He would not bleach his negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face".

In his book "The Souls of Black Folk" Du Bois gives us a picture of the horrific social and psychological effects of segregation that we don't get with Booker T Washington.

Re: Chapters 4-6: Up From Slavery

Posted: Sat May 07, 2016 10:18 am

by LanDroid

Seems there has always been a tension between gradual assimilation vs. radical confrontation.

William Lloyd Garrison Vs. Frederick Douglass (not sure about this example)

BT Washington Vs. WE DuBois

ML King Vs. Malcolm X

Black Lives Matter Vs. ...?....

Re: Chapters 4-6: Up From Slavery

Posted: Sat May 07, 2016 10:32 am

by DWill

I had not fully understood before reading the book that it was possible for whites to consider themselves supporters of blacks even though many or most were happiest with segregation. In the introduction the the edition I read, Ishmael Reed talks about the visceral fear underlying the belief in segregation, that black men would have sex with white women. Race-mixing of this degree was especially abhorrent in this era in the U.S. Prejudice against it remains, but it's much less. It could be that even blacks thought that racial mixing, which after all is what full equality would entail, was undesirable.

Re: Chapters 4-6: Up From Slavery

Posted: Mon May 09, 2016 1:56 am

by Robert Tulip

LevV wrote:His description of the Indians he is working with is interesting. He describes them as, "wild and for the most part ignorant" showing that he is also capable of holding stereotypes of other peoples.

Lev, that does not read to me as a stereotype.

It reads as a factual description of a real group of people whom BTW was personally responsible for, and whom he actually respected.

Calling this a stereotype seems to import a modern prejudice, a view that because calling people wild and ignorant supports a racial profile it must be untrue on principle.

The entire concept of civilization is one that could be cast into question by your assertion. In questioning the racist prejudices of previous eras about savagery and civility, historians these days often seem to invert the previous view, and instead regard the empires of steel and writing as more barbarous than the stone age tribes they conquered.

I prefer to read this line from BTW as an unvarnished factual description, within the context of his recognition that American civilization was the apex of human progress in his day.